What is "Content"?

"Content." A word seemingly inseparable from the modern internet, but regrettably not in its adjective meaning of "satisfied". Cambridge Dictionary defines the noun form of "content" as either "the ideas that are contained in a piece of writing, a speech, or a film" - e.g., "It's a very stylish and beautiful film, but it lacks content" - or "information, images, video, etc. that are included as part of something such as a website" - e.g., "All this cool content is available to subscribers only." Take note of the implications of those example sentences, critiquing a creative work on the one hand and advertising a product on the other.

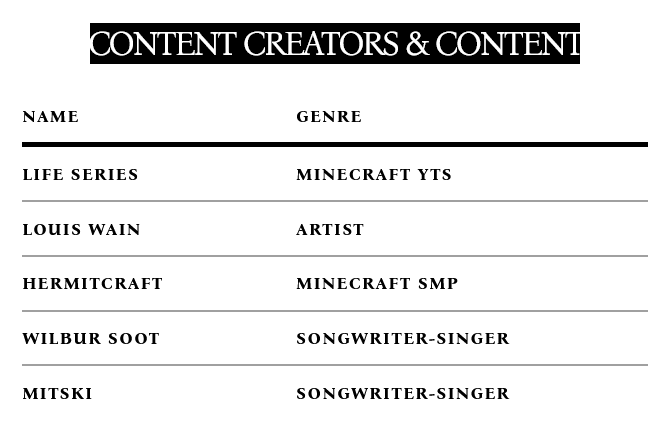

Like most Gen Z internet users, I've grown used to people describing social media posts, news articles, videos, artwork, photography, and other information or creative works as "content" to the point it usually doesn't raise any eyebrows, but something always felt off when I saw sections of websites like this:

Found under an "interests" section on someone's Carrd profile, and formatted identically to other tables on the same page - "Books & Webtoons", "Hobbies & Games", and "Anime, Movies & Shows" - this individual (kept anonymous so as to not make them a target) is using "content" as a catch-all term for creative works they enjoy that do not neatly fall under the other categories. Accordingly, the phrase "content creators" to them encompasses artist Louis Wain, singer Mitski, online streamer/YouTuber/musician Wilbur Soot, and two Minecraft YouTube series (both of which are multiplayer collaborations rather than the work of a single individual); likewise, they use "content" itself to refer to stylized cat drawings, indie music, and YouTube videos of people playing Minecraft alike. Put a pin in Mitski's inclusion in particular, as she has actually spoken about her qualms with the music industry in ways that will be relevant later. Though I'm certain the person who made this profile had no ill intent, language can be powerful, and it is worth delving deeper into what using the word "content" this way implies about the creative works being described - unwittingly or otherwise.

As with the strongly related word "consume" - the two are commonly combined into the phrase "content consumption", in fact - one of my first exposures to criticism of the concept came from Richard Stallman's writing on GNU.org. He says using the word "content" to describe works and communications "treats them as a commodity whose purpose is to fill a box and make money. In effect, it disparages all the works by focusing on the box that is full." The connotation of the term, Stallman argues, reduces creative works to commodities lacking in individual distinction or value. In the same entry he cites author and tech philosopher Tom Chatfield: "The moment you start labelling every single piece of writing in the world 'content,' you have conceded its interchangeability: its primary purpose as mere grist to the metrical mill." Both authors agree the word "content" is denigrating by implying that the purpose of any piece of writing is merely to serve as a product alongside countless other products, all interchangeable and amorphous.

However, some groups with a similar aim to GNU (which promotes "free as in freedom" software and thus often criticizes copyright) take a different approach to the word even while having a comparable philosophy. QuestionCopyright.org - the site affiliated with the "All Creative Work is Derivative" video from my artifact - has an article titled "Understanding Free Content" by Nina Paley. The article opens with the bold statement, "Content is an unlimited resource." [emphasis theirs] Paley then elaborates, "Think of 'content' - culture - as water. Where water flows, life flourishes." In contrast to physical forms of media like books and DVDs, Paley argues that information itself (and digital renditions of such) should be regarded as an aspect of culture to be freely shared rather than as property to be guarded. I get the impression that the word "content" is being used here simply as a way to generalize about various forms of information and creative works, similar to why many people use "consume" - but interestingly, the argument presented seems opposed to the corporate idea of "content consumption", even without addressing it by name.

Continuing this metaphor [of 'content' as water]: copyright monopolies are an attempt to dam up and control all the rivers, reducing them to a trickle. When Big Media succeeds locking up culture, it's like in closing off water: they get a stagnant pool that turns to poison. Fish die and mosquitoes swarm, because the water has no source to flow from nor destination to flow to.

Placing restrictions on culture - as "Big Media" corporations do when they treat "content" as a product to be consumed and bought and sold rather than an unlimited cultural resource - is equated to damming up rivers and destroying ecosystems.

This attitude reminds me of a post by Tumblr user ultraviolet-techno-ecology, since although it takes a stance against the word "content", the rationale is actually quite similar to Paley's above:

I think that a big part of the reason 'Content' has become the word of choice is because it specifically frames the subject in a way that is advantageous to corporations. Videos, music, games, and everything else on a computer is Information, and saying 'Information Consumption' immediately reveals the absurdity behind the idea of intellectual property particularly in relation to the internet. [...] ['Content' is] information - and information is shared not consumed.

Although these two pieces of writing might seem contradictory in that one endorses the word "content" while the other decries it, they are united in their opposition to the privatization and commodification of what the word refers to - digital information and creative works of various sorts.

And the corporate ulterior motive in favor of the word is indeed significant. In a 2010 TED Talk titled "How YouTube Thinks About Copyright", Margaret Gould Stewart - then YouTube's head of user experience - states plainly: "YouTube cares deeply about the rights of content owners [emphasis mine], but in order to give them choices about what they can do with copies, mashups and more, we need to first identify when copyrighted material is uploaded to our site," referring to the platform's "Content ID" system of automated DMCA takedowns. Here "content" necessarily refers to video and audio only, so then why not just say that? Because, authors like Stallman and Chatfield and ultraviolet-techno-ecology would likely argue, the word "content" reduces the topic of discussion to a product, which is clearly in the best interests of a multibillion dollar corporation - but what's best for corporations is not always what's best for artists or society as a whole.

Accordingly, YouTube as a corporation certainly doesn't speak for all of its users when it treats their videos as products. There are numerous examples of YouTubers resisting and/or criticizing the commodifying attitude shown above, but here's a rather unorthodox one: in the video essay "Plagiarism and You(Tube)" by Harry "hbomberguy" Brewis, the profit incentive for making "content" is discussed repeatedly because it is often a key motive for plagiarists. Brewis notes, "Internet video as a business is at odds with internet video as a medium, dare I say an art form... If you want to make as much money as possible in the short term, you cut those corners and you make as much product [emphasis mine] as possible." Brewis argues that treating videos as a moneymaking product, rather than a way to entertain or educate on something the creator cares about, incentivizes low-effort techniques such as plagiarism and spreading misinformation. In one instance, Brewis uses the word "content" outright disparagingly to refer to lazy, unoriginal videos whose sole purpose is to generate profit.

More saliently, a later segment in the video (around the 1:04:06 mark) analyzes the phenomenon of "content mills", which Brewis defines as "organizations which produce huge amounts of material very quickly, designed to get attention with no interest in quality." There are countless examples both in YouTube channels and in ad-stuffed websites, which overrun search engines to such a maddening extent that someone made an alternative called "Stop the Milling" specifically to exclude those results. Similar in impression to "diploma mill" or "puppy mill", the term "content mill" has been used disapprovingly in most contexts I've encountered it, but strangely, searching "content mill" on DuckDuckGo now presents numerous results promoting the business model as a sort of get-rich-quick scheme. In contrast, Chelle Stein's article "What Are Content Mills? Should You Write for Them?" - which early on drops the heavy-hitting line, "Think of content mills as the sweatshop of the writing industry", wow - addresses not only plagiarism but also low pay and stifled growth for freelance writers, among other ethical concerns.

Notice how, although writing is the actual job to be done, these sites are not called "writing mills". This is because in order for their business model to function, they must reduce writing - a form of communication and creative expression valued by humans for thousands of years - to a dispassionate, mass-produced commodity, just as many of the above authors have noted previously. If these corporations respected writing as an art form or something capable of unique value, they wouldn't be churning out the massive quantities of shoddy "content" their bottom line depends on.

Personally, writing is my lifeblood, and drawing is one of my more casual hobbies as well. To describe my writing or drawings as "content" feels depreciative and disdainful. Although I generally don't post my creations on social media, I have heard other artists lament how the demand for "content" affects their work. I discussed this with Nicole White as detailed on the Interviews page, but another notable dissertation comes from a self-improvement YouTuber I enjoy, Campbell "struthless" Walker. His video "The problem with the internet that no one is talking about" - whose thumbnail aptly features the Mona Lisa with the words this is not "content" - details the impact of the "content" mindset on artists and their artwork:

The net result is that every creative person who's posting their work online is now just called a 'content creator' and their work is now just called 'content'. My thesis is that this is a bad thing. The main reason is that the label 'content' limits creativity. By calling art 'content' our art is given a very specific purpose: serve the algorithm set out by a handful of tech companies. Instead of creative exploration, these algorithms reward art that seeks and holds attention. This is because this attention is the product that these media companies are selling; it's how they make money. Over time, by very much intentional design, the art becomes formulaic.

I couldn't have said it better myself (though holding attention may be a bit contentious, for reasons that will be explored when we unpack "consume"). Formulaic is certainly a great descriptor here, and it's an opinion likely affirmed not only by previous authors like Stallman, but also by renowned filmmaker Martin Scorsese. Scorsese lamented that the attitude of "content" as seen on streaming services like Netflix has caused the art of cinema to be "systematically devalued, sidelined, demeaned, and reduced to its lowest common denominator." He really did not hold back:

As recently as 15 years ago, the term 'content' was heard only when people were discussing the cinema on a serious level, and it was contrasted with and measured against 'form'. Then, gradually, it was used more and more by the people who took over media companies, most of whom knew nothing about the history of the art form, or even cared enough to think that they should. 'Content' became a business term for all moving images: a David Lean movie, a cat video, a Super Bowl commercial, a superhero sequel, a series episode. It was linked, of course, not to the theatrical experience but to home viewing, on the streaming platforms that have come to overtake the moviegoing experience, just as Amazon overtook physical stores.

Scorsese contrasts the modern corporate usage of "content" to its original analytical meaning, and deplores the impact this has had on the art form, equating it to other corporate trends like Amazon's commerce monopoly. His observation that works of art are now lumped in with literal commercials is particularly keen, as it ties back to why companies like YouTube are so eager to use and normalize the term.

And cinema is not the only form of art that some feel has suffered as a result of corporate attitudes. Singer-songwriter Mitski (remember her mention earlier?) has repeatedly expressed her discomfort with consumerism and related practices in the music industry, including from her own fans. On one common fan behavior - concertgoers filming the show on their smartphones - she had this to say: "When I'm on stage and look to you but you are gazing into a screen, it makes me feel as though those of us on stage are being taken from and consumed as content, instead of getting to share a moment with you." She directly contrasts having a meaningful experience with a work of art (which I'm sure some would describe as almost spiritual, given the emotionally powerful nature of Mitski's music) to "consuming content". On another occasion she called out the industry for turning her into "a product that's being bought and sold and consumed", further reinforcing the slimy connotation of the word "consume" in relation to media.

On that note, with a better understanding of the implications carried by the word "content" - reducing communications and creative works to interchangeable, mass-produced commodities to serve corporate interests - I think it's time to examine the other side of the linguistic coin: describing what we do with works of art as "consume".